The 1960s were a period of profound transformation. Across Europe, a post-war generation was questioning inherited structures, demanding greater freedom, and reimagining the role of art in society. Music, cinema, visual arts and dance all became laboratories for new forms of expression, often blurring boundaries that had previously seemed fixed. In France, this creative restlessness found one of its most striking expressions in the encounter between experimental music and modern dance, embodied by choreographer Maurice Béjart and composer Pierre Henry.

Their collaboration, which began in the mid-1950s, stands as one of the most ambitious dialogues between sound and movement of the period. Messe pour le temps présent, premiered at the Festival d’Avignon in 1967, is often seen as the pinnacle of this partnership. But it represents only one chapter in a much longer artistic relationship.

Musique concrète

Before looking more closely at Messe pour le temps présent, it is worth focusing on the essence of Pierre Henry’s art: Musique Concrète. It is often considered one of the ancestral branch of modern electronic music, and uses everyday sounds and noises as raw material. A train in the distance, a scream, a sigh, a creaking door or a raindrop — everything can become music. The recorded “sonic objects” are then transformed through techniques such as splicing, looping, reversing, changes in speed, etc.

This radical approach to composition was developed in France in the aftermath of the Second World War by engineer and theorist Pierre Schaeffer. He co-founded the Studio d’Essai within French National Radio during the war years. It was initially a resistance tool and later became the voice of a liberated Paris. The studio soon became a site of sonic experimentation. Fascinated by the expressive possibilities of recorded sound, Schaeffer began exploring new compositional methods. In 1949, he formally articulated the concept of musique concrète.

When I proposed the term “musique concrète,” I intended to point out an opposition with the way musical work usually goes. Instead of notating musical ideas on paper and entrusting their realisation to well-known instruments, the question was to collect concrete sounds, wherever they came from, and to abstract the musical values they were potentially containing.

— Pierre Schaeffer

Pierre Henry joined Schaeffer in 1949, alongside other young composers such as Pierre Boulez, Karlheinz Stockhausen and Jean Barraqué. Within the Studio d’Essai, later renamed the Groupe de Recherche de Musique Concrète in 1951, new techniques emerged, embracing the technological possibilities of magnetic tape. The engineers invented new machines to push these experiments further. The phonogène would transformed sound by altering speed, pitch and time. The morphophone was a rotating tape machine that would create an early form of looping, echo, and artificial reverberation. They also built an early version of theremin that would require a man to interact with huge induction coils with this body through space.

Meeting of two men: Béjart and Pierre Henry

It was through Symphonie pour un homme seul, composed by Schaeffer and Henry in 1950, that Maurice Béjart first encountered musique concrète. The impact was immediate and visceral. Béjart adapted the piece into a ballet, marking the beginning of a long artistic and personal relationship with Pierre Henry.

For Béjart, discovering this music was described as an emotional shock. For Henry, Béjart’s choreography revealed new ways his sounds could inhabit bodies, movement and space. From that moment on, music and dance became inseparable elements of a shared creative vision.

Complementary creative visions

From 1955, beginning with Symphonie pour un homme seul, until Messe pour le temps présent in 1967 and even further, Béjart and Henry collaborated on numerous projects. They developed a sustained dialogue between experimental sound and modern dance.

By the early 1960s, Béjart was establishing himself as a major figure in modern dance. He founded the Ballet du XXe Siècle and reached international audiences, seeking to reconnect dance with contemporary life through philosophy, ritual and modern sound worlds. This approach naturally led him to work regularly with Henry on many productions..

Messe pour le temps présent: a total spectacle

In 1967, the Festival d’Avignon opened its doors to modern dance. They invited Béjart to perform in the prestigious Cour d’Honneur of the Palais des Papes.

For the occasion, the choreographer envisioned a ballet that would encapsulate the spirit of its era. A “total spectacle”, as he would call it, involving dance, theatre, recitations and music. The piece moved through different styles and influences, drawing on Indian and Japanese traditional music and mysticism as much as contemporary electronic sounds. Dancers appeared on stage in jeans and trainers, shifting between classical vocabulary and popular dances such as the jerk.

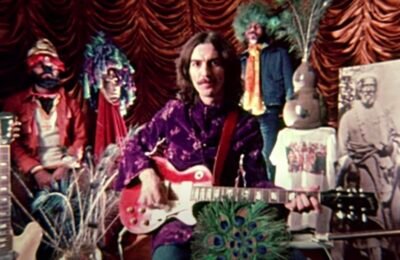

Electronic Psychedelia

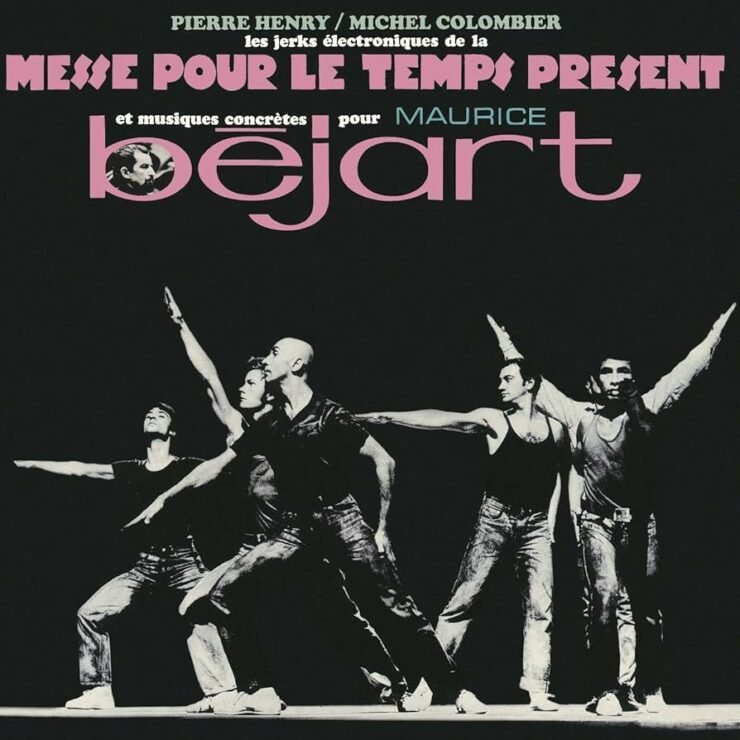

To realise this vision, Béjart once again turned to Pierre Henry. With the help of composer Michel Colombier, Henry’s sonic explorations were blended with more traditional instrumentation — drums, guitars and keyboards. Outlandish recorded noises sit alongside Colombier’s psychedelic arrangements, forming a striking and cohesive whole.

The collaboration resulted in a landmark work of psychedelic and electronic music. “Psyché Rock”, inspired by Richard Berry’s “Louie Louie”, achieved cult status, later appearing in film soundtracks, being remixed by artists such as Fatboy Slim in 2000, and famously inspiring the main theme of the animated series Futurama. In 2016, Messe Pour Le Temps Present was revisted in the Philarmonie de Paris, with Pierre Henry.

The success of the “jerks” music from Messe pour le temps présent led to strong sales of the Psyché Rock single, soon followed by the release of the album Les Jerks électroniques de la Messe pour le temps présent et musiques concrètes pour Maurice Béjart.

The album as retrospective

Rather than functioning as a simple soundtrack, the album acts as a retrospective of Pierre Henry’s work with Maurice Béjart. Alongside material from Messe pour le temps présent, it compiles compositions used for several of Béjart’s choreographic projects between the mid-1950s and the late 1960s.

These include Le Voyage (1962), inspired by the Bardo Thödol or Tibetan Book of the Dead, from which Henry composed the movement Les divinités possibles. Henry also handpicked extracts from La Reine verte (1963), for their bold use of electronic and electroacoustic processes true to the spirit of musique concrète. Finally it featured excerpts from Variations pour une porte et un soupir. This piece was built from only three sounds: a human sigh, a musical sigh produced by a musical saw, and a creaking door.

A unique approach

Sonically, the album unfolds as a rich soundscape shaped from carefully recorded noises. Henry was fascinated by the world around him, using its sounds as raw material to fashion something new. Like a sculptor shaping stone or a pop artist elevating the mundane, he transformed everyday noises into expressive musical forms. Each listener may hear — or feel — something different.

The World as Instrument

Messe pour le temps présent brought Pierre Henry’s work to mainstream attention. But it also, in some ways, confined him within a label. Shortly afterwards, he explored further collaborations within the psychedelic rock world, notably with British band Spooky Tooth on Ceremony: An Electronic Mass (1969). An experience he did not particularly enjoy, and returned to a more solitary practice.

Today, Pierre Henry is widely regarded as one of the fathers of electronic music. And a very prolific one. Magnetic tape was his canvas; the mixing desk, his brush. Reflecting on his influence on DJs and electronic artists, he acknowledged the connection, even if he sometimes felt their work could take the easy way out. Still, he embraced the idea, concluding: “Anybody can make music. It is a good thing that people become aware of the musical dimension.”