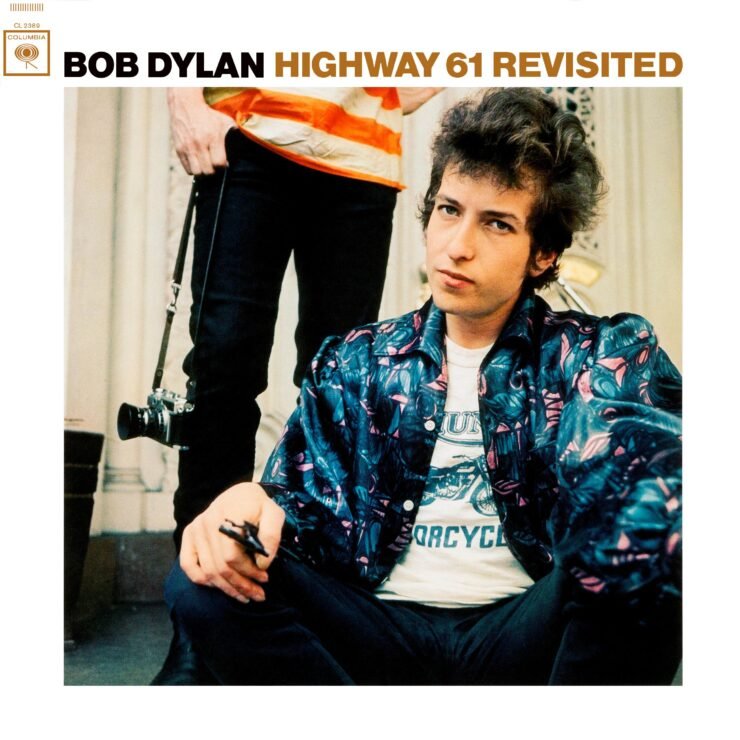

Highway 61 Revisited turned 60… and, as usual, this kind of big anniversary makes a good excuse to turn back to this kind of album and have another look at it. If not an original or fresher look, at least an honest and personal one. Because it’s easy to forget that even cultural touchstones such these are still works of art. In the most literal and less pretentious sense of the term. They are the results of artists working through their own life, their own feelings, their own technical and conceptual limitations.

A Soundtrack to “The Sixties”?

In the case of Highway 61 Revisited, it’s kinda easy to forget that as the album has become such an emblematic signifier for the Sixties. Put a needledrop of the track in a movie and immediately the audience has an idea of what to expect: hippies, Vietnam war, counter-culture, flower power, protests, psychedelia, etc. You know, these Sixties…

The irony here is that image of the Sixties actually describes maybe the last three or four years of the decade. And Highway 61 Revisited was actually written, recorded and released before they happened.

Was Dylan a precursor of the hippie movement? Did he anticipate the Summer of Love two years before it happened? When you take the time to brush off all the cultural baggage that was put on the album since it was released, the answer is very obviou. No, it is very much not an album of these Sixties. It is not an album of love, hope and joy. On the contrary, it is a deeply mean and angry album, full of smugness, and frustration, and despair… starting with its very first and most iconic song.

The Art of the Accusatory “You”

Despite its bombastic and uplifting intro, “Like A Rolling Stone” is still an incredible mean song where Dylan revels in the misery of an unnamed woman and addresses her directly. It is actually the first of the three “you” songs of the album: “Like A Rolling Stone“, “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Queen Jane Approximatively“. One could add “Positively 4th Street” that was recorded during the same sessions as the album, but released as a single. That makes it four songs where Dylan directly berates and humiliates some elusive person.

Personalizing the Accusation

Granted, it wasn’t the first time in his career that Dylan was using a song to settle some score. “Ballad in Plain D“, released on Another Side of Bob Dylan, was a horrible song slandering his ex-girlfriend’s sister. But even then, he targets her indirectly. When he sings: “For her parasite sister I had no respect / Bound by her boredom, her pride to protect / Countless visions of the other she’d reflect / As a crutch for her scenes and her society.”, he still sings about her, not to her…

In a similar way, Dylan had already use the accusatory “you” in previous songs, but it wasn’t as targeted. When he was singing “And you who philosophize disgrace and criticize all fears / Take the rag away from your face / Now ain’t the time for your tears.” in “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” or even when he addresses all the “writers and critics”, “senators, congressmen” and “mothers and fathers” on “The Times They Are A-Changin’“, he targets groups of people in general terms.

On Highway 61 Revisited, his writing targets individuals. Even if the name of the actual targets are still today a matter of theories and conjecture, which allows the songs to take a broader meaning. These singular “you” still make a difference. They are the mark of a confrontational attitude that’s symptomatic not only of Dylan but also of that very specific time of the mid-60s.

From Protest Singer to Paranoia

It is well-known that, around 1964 and 1965, Dylan was at his most misanthropic and paranoid. Between an exhausting touring and recording schedule that required him to fuel himself with amphetamines, the rejection of his traditional audience and allies due to his new sound, the attention of over-invested fans such as the infamous A. J. Weberman, it’s not difficult to understand why. Any sensitive person, even more so an artist, would probably react in the same way.

Cool Detachment and Mid-60s Attitude

But that was also something that was in the zeitgeist.

Before the rock bands of the 60s embraced flower power and positivity, there was a brief moment in the mid-60s where it was much more fashionable to look haughty and smug. Look for instance at a picture of the Byrds circa 1965. Despite the lovely harmonies they used on “Mr Tambourine Man“, they don’t look as a friendly and approachable bunch. On most of the pictures, it looks like Jim McGuinn was using his rectangular shades in the same way as Dylan or John Lennon around the same time… As a way to put a distance between him and the others.

Eventually, Dylan will let the psychedelic movement of the late 60s pass him by. Either because he was uninterested by it or because he was too burned-out to. He will famously retreat to his Woodstock house and focus on going back to the roots of American music with the Basement Tapes. But in that brief moment of 1965 and 1966, he was definitely attuned to what was hip.

And yet…

Blues as Foundation

Highway 61 Revisited seems weirdly uninterested in the musical trends and focuses of the times. For instance, it is in a lot of ways a blues album. During the recording, Dylan specifically asked to hire Mike Bloomfield due to his reputation as a Chicago blues guitarist. The lyrics are openly reusing some famous blues colloquialism.

- “I got this graveyard woman, you know she keeps my kid / But my soulful mama, you know she keeps me hid” —”From a Buick 6“

- “Well, I ride on a mailtrain, baby / Can’t buy a thrill” —”It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry“

- “Well Mack the Finger said to Louie the King / I got forty red white and blue shoestrings“— “Highway 61 Revisited“…

And that’s nothing to say of titles like “Like A Rolling Stone“, “Tombstone Blues“, “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues“… Or the title of the album itself.

Authenticity and Irony

That focus on the blues may not seem out of place, relative both to Dylan’s career and to the cultural trends of the time. First, blues musicians always had a place in the Greenwich Village music community. They were considered as the repositories of a truly authentic American musical tradition. As such, Dylan’s first major gig in New York in 1961 was opening for John Lee Hooker. Then, in 1965, the Beatlemania had paved the way for the British Invasion. It was itself incredibly focused on the blues, with bands like the Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall, the Yardbirds, etc.

But both the Greenwich Village musicians and the British Blues Boom tended to put some emphasis on the authenticity of the blues. At the time, the New York snobs may have not considered a bunch of white English lads are proper authentic bluesmen. Nevertheless, people like Eric Clapton, Keith Richards, Brian Jones or Peter Green genuinely wanted to pay homage to traditional blues. They wanted to be seen as authentically playing the blues.

On the other side, Dylan doesn’t seem to care at all.

Experimenting with Tradition

To quote Michael Gray’s brilliant book, Song & Dance Man: The Art of Bob Dylan: “If Dylan’s stance is so different from that of the white frontmen of the transglobal blues industry, the difference arises from how he feels about the potency and the eloquence of the old blues records and the expressive vernacular of the world they inhabit. This is why what Dylan wants to do with this immense, rich body of work is experiment in how he might utilise its poetry, its code and its integrity — to see how these may stand up as building blocks for new creative work — just as se (and just as the blues) uses the language and lore of the King James Bible.“

This is not something that is specific to Highway 61 Revisited. As Michael Gray points out in the chapter of his book dedicated to Dylan’s relationship to the blues, all through his career, he has commonly used the blues’ lyrical tropes and clichés and tweaked them to fit his vision. But that approach is very much at play on this album. The title itself suggests so.

Revisiting Highway 61

Not only does it reference a blues title that Dylan himself had already covered on his very first album, it clearly states that it is time to revisit it. To quote Michael Gray again, “indeed the album titte ‘Highway 61 Revisited’ announces that we are in for a long revisit, since it is such a long, blues-travelled highway. Dylan could not have chosen a more apt and accurate route, a better song to allude to or a finer emblem for his own musical journey.

Consider the many bluesmen who had been there before him, all recording versions of a blues called ‘Highway 61’ — a blues in which, ironically, one of the things that varies, puzzlingly and fascinatingly, is the described route of the highway itself!“

That’s how such a blues commonplace phrase such as “I got a woman” becomes “I got this graveyard woman“. But as Gray’s scholarly study of Dylan’s lyrics shows, Dylan’s references to the blues corpus goes much deeper than the best-known tropes. For instance, to refer to Gray’s scholarly analysis once again, the last verse of the song “It takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry” starts with the line “Now the wintertime is coming“, just like Robert Johnson’s “Come On In My Kitchen“‘s last verse starts with “Winter time’s comin’…“

Name-Dropping and Decay

For all its use of blues tropes, Highway 61 Revisited is at least quite consistent in that regard… Whereas when it comes down to the broader references and name-dropping, it’s all over the place. In “Tombstone Blues” alone, we cross paths with the US revolutionary figure Paul Revere, the female outlaw Belle Starr, Jack the Ripper, John the Baptist, a Woody Guthrie song’s character called Gypsy Davey, Galileo, Delilah, Ma Rainey and Beethoven. Bo Diddley is name-dropped in “From A Buick 6“, F. Scott Fitzgerald in “Ballad of a Thin Man“, Edgar Allan Poe’s Rue Morgue in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues“, and then Romeo, Cinderella, Cain and Abel, the hunchback of Notre Dame, the Good Samaritan, Ophelia, Noah, Einstein, Robin Hood, the Phantom of the Opera, Casanova, Nero, the Titanic, Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot all appears through “Desolation Row“.

But the amusing consequence of this accumulation of references is that it does not have the effect of elevating the lyrics to the rank of an erudite work of art that would cleverly use the semiotic complexities of these references. It just cheapens these references.

The lyrics are still brilliant pieces of allusive poetry, don’t get me wrong. But they didn’t need all these references. Take the following verse from “Desolation Row“.

Einstein, disguised as Robin Hood

With his memories in a trunk

Passed this way an hour ago

With his friend, a jealous monk

He looked so immaculately frightful

As he bummed a cigarette

Then he went off sniffing drainpipes

And reciting the alphabet

Now you would not think to look at him

But he was famous long ago

For playing the electric violin

On Desolation Row

Its evocative power doesn’t come from the first line but from the following ones. Dylan could mention anyone in the first line, the sense of downfall, decay and hopelessness would still emanate from the rest of the verse.

The Final Irony

And as the seemingly random name-dropping cheapens these references by rendering them meaningless, I’d suspect that this was very much the expected outcome. Again, Highway 61 Revisited is a very misanthropic and angry album… And the characters targeted in songs like “Like A Rolling Stone“, “Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Queen Jane Approximatively” do have in common that they were, at first, from the educated upper-class. In the songs, they are cast from their pedestals, much to Dylan’s schadenfreude. But I would argue that Dylan’s writing technique through the album seems to achieve the same outcome… As if he had been listening to the performative name-dropping of his new rich and famous milieu and was now screaming “anyone can name-drop stuff, you’re not better than anyone else just because you just mentioned Ezra Pound or F. Scott Fitzgerald!“

So what do we make of Highway 61 Revisited?

For all that has been written about it, from the minutiae of its writing and recording in Clinton Heylin’s biography of Dylan, The Double Life of Bob Dylan to Michael Gray’s laser-sharp lyrical analysis, I have to admit I’m still baffled by that album.

I get where a lot of it is coming from. I think I get what Dylan was trying to express, at the very least in a broad sense. But at the same time, I don’t get how it can be so good. The recording famously was quite a mess. Dylan didn’t have a strong musical vision for the songs. He was heavily relying on the inspiration of the hired musician around him. That was transpiring from the famous anecdote around Al Kooper’s organ line in “Like a Rolling Stone“. However, the release of the (almost) complete recording sessions in the Bootleg Series Volume 12 shows that, on most of the takes, the musicians are following Dylan but are free to improvise around his voice and his guitar.

The fact that the end result of such a chaotic writing and recording process became not only a masterpiece but an era-defining one still appears as a mystery to me. Again, it doesn’t really make sense for Highway 61 Revisited to be used as a cliché signifier for these Sixties… Even though I try again and again, I don’t understand how that album manages to integrate all its various components and works as a consistent work of art.

So what can I say…

… ultimately, not much more than it is a masterpiece.