Fifty years ago, Queen released A Night at the Opera — the record that transformed them from rising stars into one of the defining bands of the decade. It was, at the time, the most expensive album ever made, and the home of the now-legendary “Bohemian Rhapsody.” But more importantly, it was the band’s breakthrough: the moment when their ambition, craft, and sheer stubbornness finally bore fruit. Sheer Heart Attack had given Queen their first taste of international attention with “Killer Queen,” yet behind the scenes, the band was earning little more than pocket change. A Night at the Opera was not just their fourth album — it was a make-or-break gamble.

You would think that with the commercial success of Sheer Heart Attack, and a worldwide hit single like “Killer Queen”, the band would be rolling in cash… But like many before them — Rolling Stones, Small Faces, or Jimi Hendrix to name just a few— Queen had had the misfortune to strike a bad deal early in their career.

The Trident Chains

Back in 1972, they met with Norman Sheffield from Trident Studios. He offered them a management deal with a Trident subsidiary — Neptune Production— that would allow them to make use of the studio’s hi-tech facilities while the production would look for a deal to release albums. In the fine print, it meant that the band was earning wages, producing albums. And Trident was selling them to labels, making profits. Despite the commercial success of Sheer Hear Attack and “Killer Queen”, the band kept earning the same measly £60 a week. As Trident was claiming to have invested £200,000, for promoting the band, they started reducing their wages to make up for it.

On their return from touring Japan, where they were treated like royalty,Queen quickly faced the hard, cold reality at home. Brian May laid down his guitars in his cramped bedsit. Roger Taylor returned to a flat with no running water. And Freddie Mercury tried to rest his vocal cords in a damp, chilly apartment. Matters reached a breaking point when Sheffield refused a £4,000 cash advance for newlywed John Deacon, who couldn’t afford a house deposit. Meanwhile, someone on the management team enjoyed a brand-new Rolls-Royce. They had to break free.

Reclaiming Their Future

With EMI’s help, the band hired lawyer Jim Beach to extricate them from this deal. After a nine-month dispute —while still touring Sheer Heart Attack— they had finally cut the chains. It allowed them to regain control of their back catalogue, and sign directly with EMI. But this didn’t come without any concession. Because of the sum Trident claimed to have invested, EMI paid half on the band’s behalf to buy out their contracts, and conceded 1% royalties on their next six albums! The deal left the four musicians with a bitter taste in the mouth.

Queen was now free… but still broke. Although they were eager to stop touring and start working on their new album, the band didn’t have any other choice but to keep touring for another month to replenish their funds. As Taylor would admit in an interview, they « simply couldn’t afford not to ». Meanwhile, the band was in need for a new manager. One that would take them seriously, and make them a priority. For a moment, they considered asking Peter Grant, Led Zeppelin’s manager. While Grant was eager to take them under his wing, and offered the band to be signed with Led Zeppelin’s own label Swan Song, the band opted not to hire him. They feared that Grant would make Plant, Page & co his first priority and leave Queen on the back burner.

The Making of a Monster

Eventually, they contacted John Reid, who was then managing Elton John. At first the manager was reluctant to take on another band. However, when he realised it was Queen, he accepted straight away. Quickly, he advised them to go back in the studios and record the best album they could, while he took care of business. And as he was still managing Elton John, he asked Peter Brown to assist him and focus entirely on Queen. After they finished touring, in the summer 1975, the band gathered in a house rented specifically for them. For three weeks, they rehearsed, letting their creative spirits converge as they wrote new material.

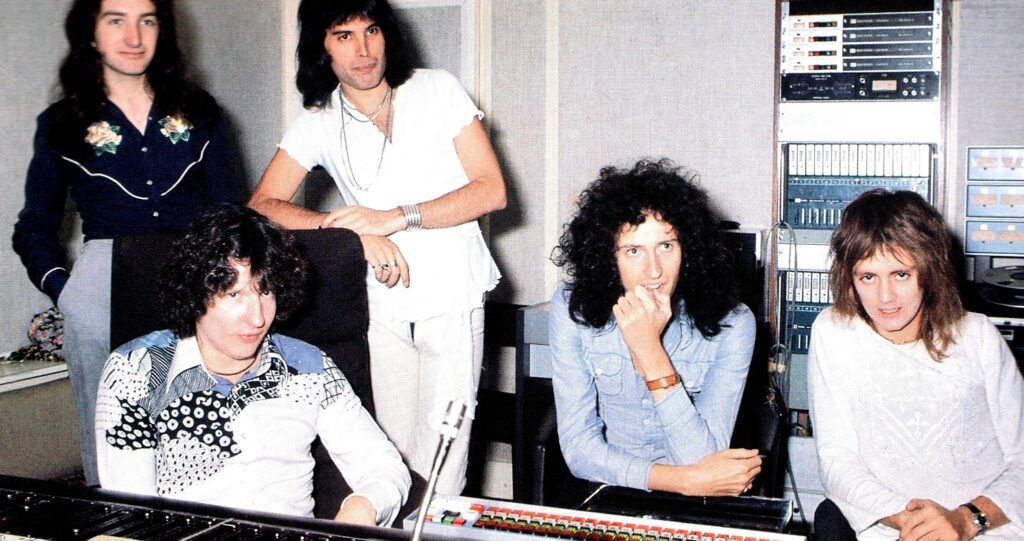

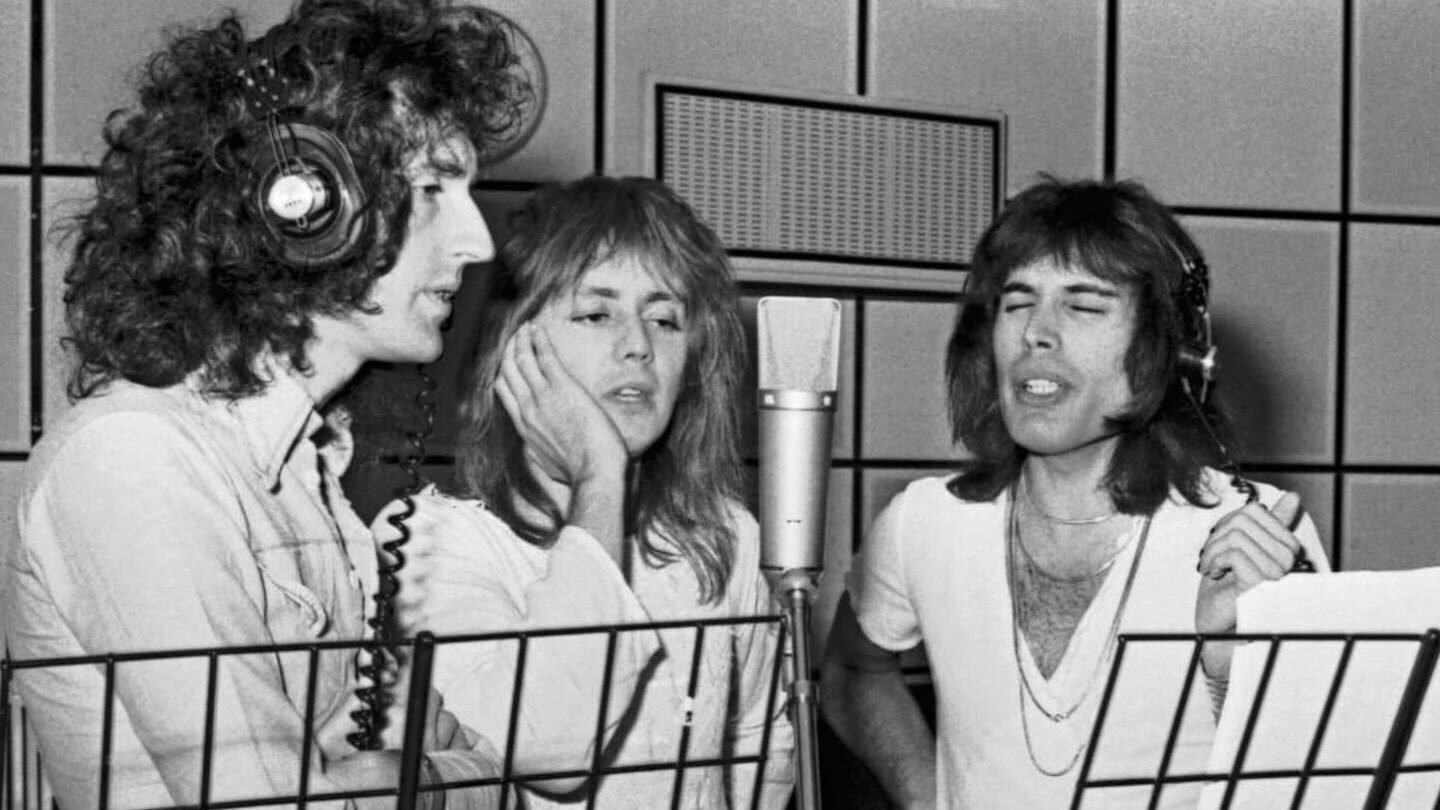

Starting from August, they started recording, going through no less than six different studios. Each studio was being used for various parts of the recording process. They started rehearsing and piecing everything together in the Ridgefarm Studio. Then they moved to Rockfield Studios in Wales. John Reid poached Roy Thomas Baker from Trident, as he had good working relation with the band on their previous albums. There, they laid down the base for each song: piano, bass guitar and drums are caught live. Guitars and vocals were recorded in Sarm East Studios, while the vocal overdubs were taped in Sarm East, Roundhouse, Scorpio and Landsowne studios. To make the best of an already expensive process, the band was split in smaller groups to allow them to focus on their own composition, in parallel.

Inside the Opera

The process took four month to completion. It cost over £40,000 (worth ten times more today), making it the most expensive album to be produced at the time. But in the end, A Night At The Opera —which took its name from the Marx Brothers’ movie— is simply astonishing. Queen extends their palette of sounds incorporating a wide range of influences to their music. They take genres that usually would have nothing to do together: Skiffle, Folk, Music-Hall, Jazz or even Opera. If, perhaps on paper, it sounds dubious, in Queen’s hands, it is just another kind of magic… Everything comes together as one. It is grandiloquent and pompous but delicate and subtle at the same time. It is Queen’s sound as we know it today. They just had unlocked the secret recipe to their signature sound… And success.

“Death On Two Legs”: A Venomous Overture

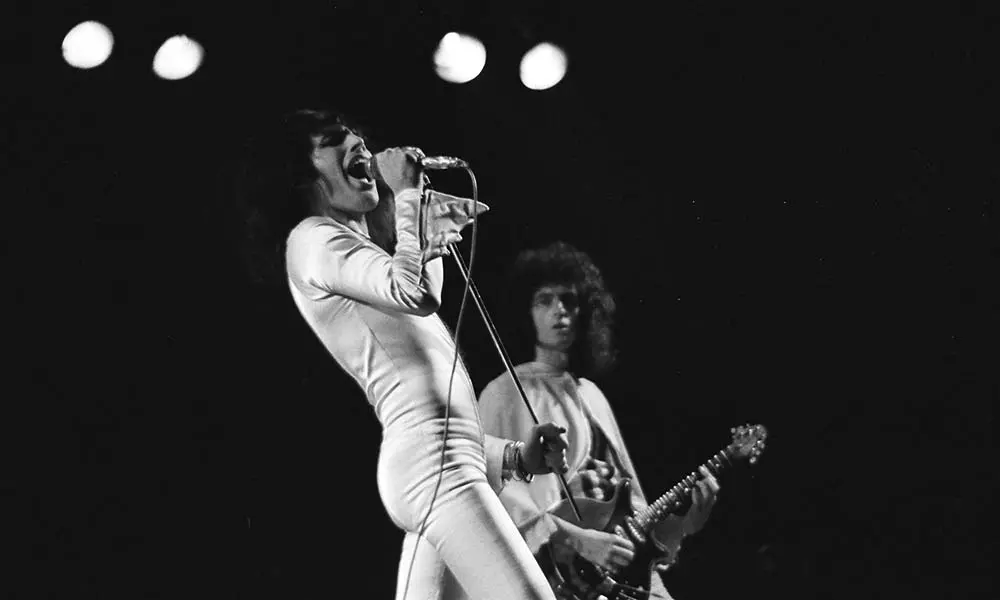

Queen don’t ease you gently into A Night at the Opera — they bite first.

“Death on Two Legs” is Freddie Mercury’s venom-laced farewell to Norman Sheffield. It also is the perfect bridge from the band’s real-world frustrations into the album’s unapologetic theatricality. The song starts with an ominous piano chord progression and threatening guitar building up to a blast before briefly calming to a jagged piano flurry and snarling guitar.… Mercury sings: « You suck my blood like a leach / You break the law and you breach / (…) You’ve taken all my money, and you want more »… The tone is sharp, the anger palpable. He continues: « You’re just an old barrow boy / Have you found a new toy / To replace me »… The lyrics are vitriolic. Without naming him, Mercury is cutting him a new suit. « You’re the king of the sleaze / (…) Was the fin on your back part of the deal (shark) »…

When Anger Finds Its Voice

To get himself into character — and to reach the song’s vicious high notes — Mercury insisted on having the playback full blast in his headphones. Engineer Gary Langan later said this treatment made Freddie’s ears bleed; Freddie claimed it was his throat. Either way, he threw himself into the performance with total abandon. When EMI heard the song for the first time, they didn’t feel comfortable, smelling trouble. Even Brian May felt uneasy about it, but Mercury wouldn’t have it any other way. “Death On Two Legs” had to stay. Vengeance is a dish best served cold, and it was the perfect occasion to settle the score.

A Lawsuit Waiting to Happen

Shortly before the release of the album, the Trident producer got wind that the new Queen album featured a very nasty song about him. And of course, business being business, he threatened EMI to sue and block the release of the album. The matter was settled out of court — meaning Sheffield profited from Queen’s creativity one last time. But, if Mercury didn’t name him, it was now pretty clear who the song was about. During live performances, the singer makes no mystery about it. He introduced the song to « a real motherfucker of a gentleman » or « a motherfucker I used to know ».

“Lazing on a Sunday Afternoon”: Vintage Whimsy

After so much fury, Queen slams the brakes with “Lazing On A Sunday Afternoon”. The song’s vaudeville mood contrasts sharply with the anger of the opener, and Mercury’s tongue-in-cheek lyrics add a whimsical touch. The vocals sound as if they are coming from an antique gramophone. This was achieved in gloriously low-tech fashion. The team played Mercury’s vocal take through headphones placed inside a metal bucket. Then they recorded the sound bouncing around inside it with another microphone. Instant vintage charm. The track lasts barely over a minute, but doesn’t need more. It lighten the mood with humour after an heavy opening. It then transitions into further oddities with guitars mimicking a revving engine, and then the roar of a real one…

“I’m in Love with My Car”: Taylor’s Roaring Love Song

“I’m In Love With My Car” is drummer Roger Taylor’s contribution, inspired by and « dedicated to Johnathan Harris, boy racer to the end »… Harris was one of the band’s roadies. A man who cherished his Triumph TR4 like it was the love of his life. The track features heavy rock riffs and a searing solo, driven by a pounding rhythm and Taylor’s raspy rocker voice, and ends with more revving engines (coming from Taylor’s Alfa Romeo).

When Brian May first heard the demo, he thought it was a joke. Who could blame him when you listen to the passionate lyrics expressing tender feelings to the piston driven machine? « When I’m holding your wheel / All I hear is your gear / With my hand on your grease gun ». Taylor was so proud of his masterpiece that he insisted to have it released as the B-Side for “Bohemian Rhapsody”. Mercury wasn’t thrilled about the idea, but it happened anyway — and today the song holds its place proudly in the band’s repertoire.

“You’re My Best Friend”: Deacon’s Sunlit Ballad

John Deacon also contributed, dedicating a song to his bride. “You’re My Best Friend” is a warm, instantly uplifting ballad carried by bright Wurlitzer chords and rich vocal harmonies — a simple idea executed with real charm. Mercury, however, was famously snobbish about the electric piano parts. Deacon was a novice player experimenting with a Wurlitzer, and the singer thought it sounded cheap. Regardless, Deacon’s melody was too good to ignore, and the track was chosen as the album’s second single. It went on to become one of the band’s most enduring hits — and one of my personal favourites.

“’39”: May’s Space-Time Folk Tale

What comes next is one of Brian May’s most beautiful pieces. “’39” is built on a gentle, folk-driven melody led by May’s 12-string guitar. Mercury and Taylor add warm harmonies behind his lead vocal. The future doctor in astrophysics draws on his passion for science to craft a sci-fi narrative inspired by Einstein’s theory of relativity: a group of space explorers leave on what feels like a one-year mission, only to return and find that a century has passed back on Earth. Taking up a challenge from May, John Deacon even learned to play the double-bass in just a couple of days for this track.

“Sweet Lady” & “Seaside Rendezvous”

“Sweet Lady” snaps the album back into hard rock mode — sharp riffs, a slightly off-balance rhythm, and May tearing his Red Special like mad. The track gradually fades out to the closer of the album’s first side. “Seaside Rendezvous” is a delightfully nonsensical music-hall piece, with fast-paced piano and a punchy drumming. During the bridge Mercury and Taylor embark on a fantastic instrumental moment with only their voices. The singer mimics the sound of various woodwind instrument like a clarinet, while the drummer does the brass instruments, even a kazoo and casually hits the highest note on the album. The pair even break into fake tap-dance, hitting the mixing desk with thimbles on their fingers.

“The Prophet’s Song”: Apocalypse in Canon

After the whimsical nonsense of “Seaside Rendezvous”, Queen shift gears dramatically as we flip the record. Although it is the longest track, “The Prophet’s Song” is probably one of the most overlooked track of the album — or the band’s repertoire. Brian May pens another fantastically themed prog-rock epic. It tells of seers on moonlit stairs prophetising the end of all to the people of the earth. He explained that song came to him after a dream he had about the Deluge, and as a reflection of the ever growing pace of progress contrasting with a dramatic loss of human empathy.

The song opens with steady rhythm as May strums his guitar ominously. As it progresses, the guitar work and vocal harmonies intensify. It builds toward a mid-song climax where all instruments drop away, leaving Mercury’s voice to soar in a breathtaking canon. This eventually gives way to another canon, this time set against a strong instrumental backdrop. Brian May spent days in the studio in solo to assemble this ambitious piece. The song quiets at the end, with a few strings repeating the main theme, before seamlessly segueing into the next masterpiece: “Love Of My Life”.

“Love of My Life” : A Heart Laid Bare

Legend tells us that Mercury wrote this heartfelt love ballad for the love of his life Mary Austin, who stood by his side until the end, despite his love for men. According to manager John Reid however, the song was inspired by David Minns —Eddie Howell’s manager— with whom Mercury fell in love. Regardless of its muse, “Love Of My Life” remains one of the most powerful songs in Queen’s repertoire.

During live performance, Mercury used to let the audience sing the lyrics in an intense moment of communion, while he played piano and May accompanied on 12-strings guitar. On the album however, Brian May doesn’t play the 12-string. Mercury insisted on using a harp, so May purchased one and set about learning it… The experience, however proved frustrating. The tricky instrument constantly went out of tune. They had to record it one chord at a time and retune between takes. Fed up, May eventually adapted the song for the 12-string for live performances.

“Good Company”: A Dixieland Illusion

After this tender moment, Queen return to their flair for sonic experimentation. “Good Company” opens with Brian May strumming a gentle, old-fashioned tune on his father’s ukulele-banjo, before revealing another tour-de-force. Using only his Red Special, overdubbed through a Deacy Amp —designed by John Deacon and later commercialised by Vox as the Brian May amplifier— he painstakingly recreates an entire Dixieland jazz band. May builds the arrangement piece by piece: clarinet-like leads, trombone slides, even a tuba line, all sculpted through meticulous tone shaping —one of his specialties. It’s one of the album’s quiet miracles — a reminder of Queen’s obsession with craft, and of May’s singular musical imagination.

The Masterpiece: “Bohemian Rhapsody”

But this tour-de-force is quickly overshadowed by what comes next —the moment the entire album seems to have been pointing toward. Freddie had been nurturing this idea for years, dating back to the days when Queen were still called Smile. He would play fragments for friends and bandmates, always ending with the same enigmatic tease: “And that’s where the opera part comes in.” The first time producer Roy Thomas Baker heard this, he didn’t blink. Unlike most people before him, he didn’t think Mercury was joking. Baker had recorded opera in studios before, and he was definitely opened to experiment with rock music at that scale.

190 Overdubs Later

“Bohemian Rhapsody” was conceived in three acts: a ballad, an operatic middle section, and a final hard-rock climax. Bringing such a complex project to life was a monumental challenge. Each act was recorded separately, leaving enough blank space on the tape to fit the next part. For each part, multiple tracks are recorded for the different instruments to layer it later on the mixing process. For the opera part, Taylor sings the tenor parts, while May takes on the lower register, and Mercury handles the baritone lines. In the end, a total of a 190 overdubs were recorded and assembled. During the final mixing process, the master tape had been bounced so many times that it became dangerously thin. It was very close to tearing apart.

Anatomy of an Epic

The result is one of the most epic construction in rock history. It opens on a slow introduction with rich harmonies and grand piano arpeggios, and then transitions to the ballad with the famous « Mamaaa, just killed a man ». It then builds up adding gradually whirling guitars, steady rhythm. Suddenly it breaks out into the grandiose operatic middle section introduced by a pair of piano chords and faint, shimmering guitar harmonics. At its climax, the soaring vocal lines melt seamlessly into the wail of May’s Red Special as the track detonates into a thunderous head banging hard-rock passage. Finally, it quiets again: piano, a gentle guitar, Freddie’s last whisper — “Any way the wind blows.” A gong fades into silence.

If the lyrics may seem mysterious, it didn’t bother the singer who left it open to anyone’s interpretation. According to radio DJ and friend Kenny Everett, Mercury confessed to him that it had actually no meaning whatsoever, it was just « random rhyming nonsense ».

Forcing EMI’s Hand

When the song was finally put together and the band finally heard it in its entirety, everyone was literally gobsmacked, realising they had just made history. Freddie knew immediately that it was single material and pushed for it to be released as such. Management disagreed. EMI disagreed. Even John Deacon hesitated. Elton John — then also managed by John Reid — tried to talk Freddie out of it. Releasing such a long piece, without a proper chorus —the usual pop format— was very risky. Baker was one of the few who backed him.

To prove his point, Freddie let his friend Kenny Everett ‘steal’ the recording to play it on radio. The very next day, the DJ played the song at least fourteen times. The phone of Capitol Radio then rang off the hook with fans calling to know when the new Queen single would be released. With such public demand, EMI had no other choice. “Bohemian Rhapsody” was released on 31 October.

Long Live Queen

A Night At The Opera, was released on November 21st and was an instant hit on the global scale. After the ordeal with Trident, which had left them broke and close to the end as a band, this success came as a relief. “We had made hit records but we hadn’t had any of the money back and if A Night at the Opera hadn’t been a huge success I think we would have just disappeared under the ocean someplace. So we were making this album knowing it was live or die” confessed Brian May in 1990.

Reid had told them: « Make the best album you can », and they did. They didn’t choose the easy route. Queen spared no risk and tested their own limits. Every experiment, every vocal stack, every oddball challenge they threw at themselves was a gamble they could not afford to lose. If they began fighting for survival, they ended as champions.

It is only fitting then, that the last track recorded in Trident Studios, closed the album: “God Save The Queen”, the national anthem, rearranged by Brian May. Queen chose the perfect way to close a chapter, and in doing so crowned themselves in rock n roll history.