George Harrison’s Ding Dong, Ding Dong has often been dismissed as a seasonal curio — a festive footnote in a catalogue otherwise filled with spiritual searching, quiet introspection, and musical depth. Yet beneath its chiming simplicity lies a song deeply rooted in Harrison’s world: his home, his philosophy, and a pivotal moment of personal transformation. More than a novelty, Ding Dong, Ding Dong is a statement of intent: optimistic, symbolic, and unmistakably Harrison.

Friar Park: Where the Song Was Already Written

When George Harrison purchased Friar Park in 1970, he didn’t just buy a house — he inherited a world. Built by the eccentric lawyer and illustrator Sir Frank Crisp, the estate is famously covered in inscriptions, wordplay, and philosophical riddles carved into walls, fireplaces, and garden buildings. Crisp’s presence loomed large over the property, and soon over Harrison’s imagination as well.

Harrison would later pay direct tribute to Crisp on All Things Must Pass with Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let It Roll), and continued to mine the house’s inscriptions for lyrical inspiration. Lines such as “Scan not a friend with a microscopic glass” later found their way into The Answer’s at the End (1975).

For Ding Dong, Ding Dong, the inspiration was strikingly direct. On either side of a fireplace, Harrison noticed two inscriptions: “Ring out the old” / “Ring in the new” on the left, and “Ring out the false” / “Ring in the true” on the right.

Not far, etched around matching windows in a garden building, another phrase completed the thought: “Yesterday, today was tomorrow / And tomorrow, today will be yesterday.”

That was it. The fastest song Harrison ever written. The song’s philosophy was already there. Harrison simply gave it a melody. Beyond these lines, the lyrics barely expand — the repeated “ding dong, ding dong” mimicking the chime of bells ushering change.

Building a Wall of Sound

Musically, Ding Dong, Ding Dong draws heavily from Phil Spector’s famed Wall of Sound, particularly his festive classic A Christmas Gift for You from Phil Spector. Some have suggested Harrison was aiming for his own seasonal hit, shaped by the glam-era optimism of the mid-’70s and contemporary chart successes like Slade’s Merry Xmas Everybody and Wizzard’s I Wish It Could Be Christmas Everyday.

To realise this dense, celebratory sound, Harrison assembled an impressive cast of collaborators: Ringo Starr, Ron Wood, Mick Jones and Gary Wright (Spooky Tooth), and Alvin Lee (Ten Years After), among others.

Yet behind the exuberance, Harrison was pushing himself to the limit. 1974 was a relentless year — launching Dark Horse Records, producing albums for Ravi Shankar & Friends and The Splinter, touring, and recording his own album. His voice, already strained during the tour, grew increasingly hoarse, and he eventually contracted laryngitis. Despite this, Harrison pressed on, determined to deliver the record on time.

Ringing in the New — Literally and Spiritually

Released at the turn of the year, Ding Dong, Ding Dong feels perfectly tailored to New Year’s Eve. But for Harrison, its message went far deeper than seasonal cheer. He later described the song as “very optimistic”, adding:

“Instead of getting stuck in a rut, everybody should try ringing out the old and ringing in the new… People sing about it, but they never apply it to their lives.”

At the time, Harrison had plenty of “old” to leave behind. His marriage to Pattie Boyd had ended, and the signing of the Beatles’ legal agreement had finally sealed the band’s dissolution. Harrison was open about his shifting priorities, famously admitting, “I was losing interest in being fab.”

This was reflected in his 1974 tour, where he was criticised for foregrounding Indian-inspired music over Beatles material — playing just four Beatles songs, and even those reshaped to fit his evolving musical identity. Ding Dong, Ding Dong captures that moment of transition: not rejection, but release.

A Symbolic Farewell in Film

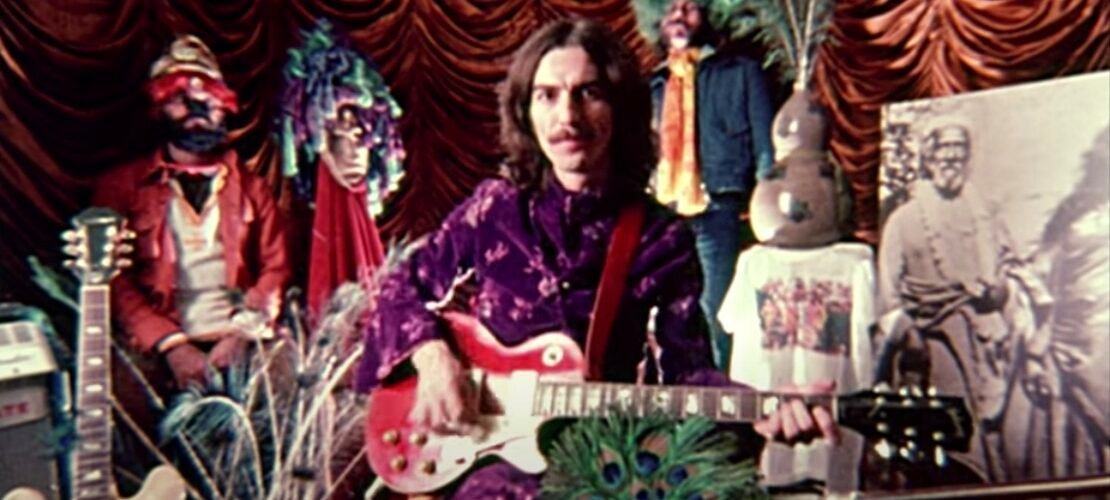

The promotional video for Ding Dong, Ding Dong was a first for Harrison — and a revealing one. Shot at Friar Park, it visually reinforces the idea of transformation. Harrison appears in outfits representing different Beatles eras: Hamburg leathers, tailored grey suits, the Sgt. Pepper uniform. He plays the guitars associated with each phase, even nodding cheekily to John and Yoko’s Two Virgins artwork.

But the most striking moment comes at the end. Standing atop Friar Park, Harrison lowers a Jolly Roger flag and raises his yellow-and-red Om banner. At the time, Harrison used these flags as personal symbols: the Om flag flew when he felt aligned with his spiritual path; the pirate flag when he did not.

Hoisting the Om flag in the video is a quiet but powerful statement — an affirmation of truth, renewal, and optimism. The old is gone. The new has begun.

Reception: A Missed Moment

Despite its charm, Ding Dong, Ding Dong never quite found widespread acclaim. It charted respectably but hovered around the Top 30, and critics were often unkind, dismissing it as repetitive, lazy, or inconsequential. The choice of B-side — I Don’t Care Anymore — hardly helped the single’s image, unintentionally reinforcing accusations of complacency.

Yet time has been kinder to the song than its initial reception.

Ring Out the Old, Personally

For me, Ding Dong, Ding Dong is the song I reach for when the clock strikes midnight on New Year’s Eve. It’s simple, yes — but perfectly assembled. Its message is clear, optimistic, and deeply human, carrying exactly the kind of hope you need when facing a fresh year and its inevitable resolutions.

Musically, it’s warm and endearing; lyrically, its ad-libbed chants invite an unguarded singalong. Add a glass of champagne, and you have the perfect New Year’s anthem.

Happy New Year.