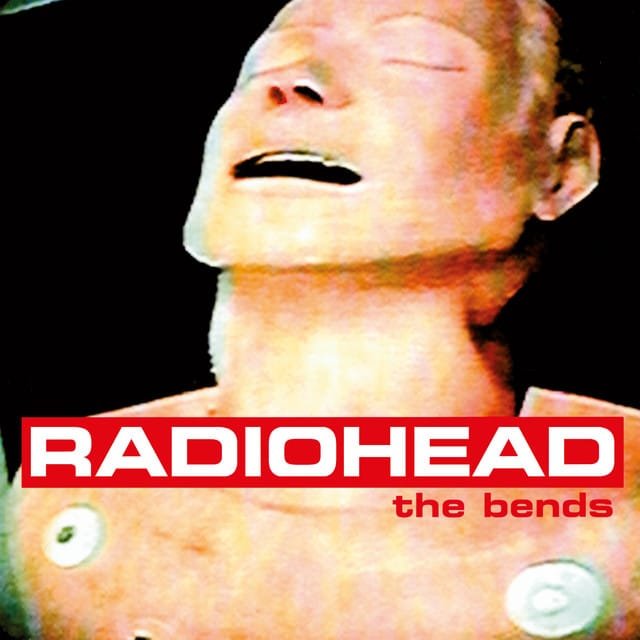

A Masterpiece Born from Pain and Perseverance

One day at school, a long time ago, I noticed a quote on my friend’s pencil case: “I used to fly like Peter Pan / All the children flew and I touched their hands.” I asked him about it. He told me, “It’s a quote from ‘Bones,’ a song by Radiohead on The Bends.” The band was just about to release Kid A, and my friend was very excited about it. When I told him I didn’t know Radiohead very well, maybe this one song Creep from a while back, his jaw dropped to the floor and he let out a scream of disbelief. “Whaaaaaat? This can’t be!”

The very next day, he gave me a mixtape retracing the band’s career. It turned out I knew a few more songs by this band from the radio. I just had never made the connection with that grunge-sounding band singing Creep in 1993. The mixtape obviously had the expected effect on me. Soon enough, I was rediscovering the band, starting with the album that had been featured on my friend’s pencil case. The Bends melted my mind and left an indelible mark. This second album was a turning point in the band’s career, and they went through hell to bring this masterpiece to life.

Breaking Free from Creep

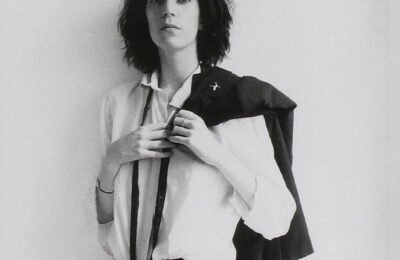

Although my lack of taste in the early ’90s was clearly to blame, I wasn’t the only one who dismissed Radiohead as a one-hit wonder. No other single had truly left a mark from their debut album, Pablo Honey. Their label reps sent them from TV show to TV show, where they were repeatedly asked to play (or mime) the same song. It got to the point where the band was sick of it, and Thom Yorke even started calling Creep “Crap.” They toured extensively to the point of exhaustion, supporting acts like Belly and PJ Harvey, playing festivals, and pushing themselves to the limit. Yorke vented to NME after canceling their set at Reading: “I’m fucking ill, and physically I’m completely fucked, and mentally I’ve had enough.”

The Pressure to Deliver

The pressure was immense. It has even been reported that EMI laid down an ultimatum: “Get sorted or get dropped.” Keith Wozencroft, head of A&R, denied this. He claimed that the label saw potential in the band and believed they were “developing brilliantly from Pablo Honey.” Paul Q. Kolderie, who co-produced the debut album, recalled Yorke playing a demo tape for him after they finished recording. The working title was The Benz. He was floored: “We’d been struggling to come up with material, so I was a little shocked when suddenly he pops out a batch of songs that are all better than anything on Pablo Honey.”

Recording The Bends

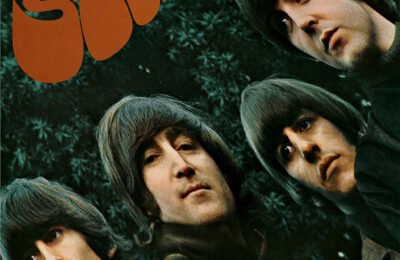

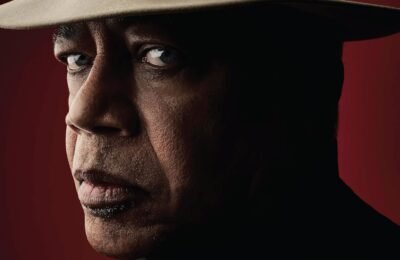

To produce their new album, Radiohead chose John Leckie. He had previously worked with The Stone Roses. The Oxford band, however, was more impressed with his work with Magazine on Real Life in 1978. Since Leckie was busy producing Ride’s Carnival of Light, Radiohead found themselves a barn in an Oxfordshire fruit farm to start rehearsing their new material.

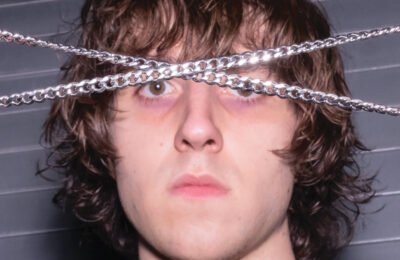

In February 1994, EMI booked RAK Studios in North London for nine weeks for the band and Leckie. The working relationship with Leckie went great. Jonny Greenwood recalled, “The best part about working with John Leckie was that he didn’t dictate anything to us. He allowed us to figure out what we wanted to do ourselves.”

However, the RAK sessions didn’t go so well. The label’s plan was to release an album by October that same year, and the band was tasked with prioritizing a single. The problem was that no one could agree on which song was suitable. Nothing they tried felt right—they were struggling to find the sound they wanted. Jonny experimented with many different instruments before returning to his usual Telecaster and sticking with it.

A Creative Turning Point

Tensions were high, and the mood was deteriorating. Thom Yorke remembered, “We had days of painful self-analysis, a total fucking meltdown for two fucking months.” Colin Greenwood described the sessions as “eight weeks of hell and torture.” According to John Leckie, toward the end of the nine weeks, The Bends was closer to being scrapped than anything else.

A noticeable turning point came when Jeff Buckley performed in Oxford, and the band went to see him. “He just had a Telecaster and a pint of Guinness,” recalled Colin Greenwood. “It was just fucking amazing, really inspirational. Then we went back to the studio and tried an acoustic version of ‘Fake Plastic Trees.’ Thom sat down and played it in three takes, then just burst into tears afterward.” The band built around Yorke’s take, and that is what ended up on the album. It was a satisfying conclusion to what seemed to have been an ordeal for the band. “There was one stage… when it sounded like Guns N’ Roses’ ‘November Rain,’” recalled Ed O’Brien. “It was so pompous and bombastic, just the worst.”

A break-through on stage

As the RAK sessions ended and the October deadline was abandoned, the band left for a tour across Europe, Japan, and Australasia. It was an opportunity for them to take a step back, try out the new material in front of an audience, and find themselves as a band again. In May, Radiohead played at the Astoria in London. The concert was filmed by MTV, and John Leckie was recording. The performance was so strong that, upon listening to the recording, the band decided to keep the footage of My Iron Lung for the album. This was one of the songs they couldn’t get right in the studio, yet here, on stage, everything just clicked. Apart from the vocals, which were re-recorded, the track that ended up on the album (and as a single) is exactly the unedited Astoria performance.

Finalizing the Album

The band returned to the studio for short sessions spread over the following months, between The Manor Studios, at home in Oxfordshire, and Abbey Road. Their time on the road had helped them find what they were looking for, and the sessions went much smoother. Songs that had caused so much frustration—like Sulk, (Nice Dream), or Just—came together more naturally. The band, which had previously played all guitars at full volume on Pablo Honey, learned to divide the work between their three guitarists. Thom handled rhythm guitar, Jonny took care of lead parts, and Ed experimented with unusual guitar effects.

EMI, however, was growing concerned about how the album was progressing. Leckie was taking his time mixing, and deadlines were approaching. The label eventually brought in Sean Slade and Paul Kolderie to help mix some tracks. Since the pair had produced Pablo Honey, EMI felt more confident in their involvement. In the end, only three tracks on the final album were mixed by John Leckie. He had mixed feelings about the decision. “The final mixes are a bit brash,” he said. “They’re kind of, ‘Zing! Look at me!’ Which I didn’t think the band wanted. I went through a bit of trauma at the time, but maybe they chose the best thing. It was just unfortunate that they didn’t tell me.”

The Release and Impact of The Bends

And here we are: 13th March 1995. My Iron Lung, released in November 1994, peaked at #24 on the UK charts with minimal promotion. High and Dry, the other single released just before the album, landed at #17 in the UK and peaked at #78 in the US. Nobody is expecting much. The trend is grunge or Britpop. Radiohead is neither. And yet…

From One-Hit Wonder to Visionary Band

The Bends takes everyone by surprise. This is no longer a one-hit-wonder. We are now witnessing a genre-defining band, about to change the face of rock music. Radiohead had finally found themselves, and they were delivering their manifesto to the world.

From the first notes of Planet Telex to the last whisper of Street Spirit (Fade Out), Radiohead crafts a sound that is both more electric and more melodic. The album showcases the full extent of their musical palette. While each song is not necessarily a potential hit single, every track has the potential to become an anthem. Each song is so emotionally charged that it grabs the listener by the gut and refuses to let go.

But the shadow of Creep still loomed. My Iron Lung, an explosive, borderline hard-rock track, served as a cynical reflection on the song that made them famous. The iron lung metaphor captured their frustration: Creep had kept them alive but left them feeling trapped. Their relationship with the label was a strange one: they were trusted to create great music, yet pressured to deliver another Creep. The final line says it all:

“This is our new song, just like the last one, a total waste of time.”

Expanding Their Sound – And Clashing with the Label

Just, mostly written by Jonny Greenwood, features an epic chord progression. Thom Yorke once said that Jonny “was trying to get as many chords as he could into a song.” It constantly alternates between calmer moments and explosive guitar surges, always building in intensity—a sound that would become a Radiohead trademark.

Yet, not all creative decisions were in their hands. The label, worried about commercial success, insisted on including High and Dry. The song was old material. Thom Yorke had performed an early version of it in a former life with a band called Headless Chicken, and recorded a demo later on with Radiohead before Pablo Honey even came to be. The band considered it as a bad song, and simply dismissed it: “too Rod Stewart”. But they had to play the game, patiently waiting they would carry enough weight to simply send the label reps kick rocks.

The Voice That Defined a Generation

Throughout the album, Thom Yorke’s vocals are mesmerizing. He displays an astonishing range—both musically and emotionally. Fake Plastic Trees is probably the best example, as mentioned earlier, but Bones and Street Spirit (Fade Out) also stand out. Yorke puts everything into his performance, treating his voice as an instrument of its own.

A Legacy That Would Only Grow

The Bends ultimately peaked at #6 on the charts—believe it or not, the lowest-ranking of all Radiohead albums. And yet, it is often regarded as one of the greatest albums of the ’90s. After months of turmoil, trying to escape the box everybody was trying to put them, and meeting the demands of their record label, Radiohead finally found their way. They ultimately did what they liked rather than what was expected of them. And by doing so, they created a music no-one had heard before, and influenced many bands.

The Oxford quintet proved they knew how to reinvent themselves. When they embarked on an extensive tour to support the album, they already had their sights set on the next one. Yorke had a few new songs in the works, and during the tour, they began adding them to their setlist. Lucky and No Surprises would go on to feature on their next album—an album that would be considered the greatest of the decade: OK Computer.

But that is a story for another time.

One thing was certain: they definitely belonged here.