The other day, my beloved was in a rebellious mood. Chin up, fist raised, she was singing: “My name is James Connolly, I didn’t come here to die!”

“Honey,” I said, “what are you on about? And who the feck is James Connolly?”

“Oh, it’s a song by Black 47! And he is the one we should have had,” she replied, launching into a passionate tale about a great Easter Rising leader.

In case you missed an episode—I’m not Irish. And while I know about the 1916 Easter Rising, I’m no expert on its key figures. But as a Frenchman, I love a good revolution—and I love a good punk protest song.

Who is James Connolly?

For those who, like me, didn’t know the man, let me introduce him.

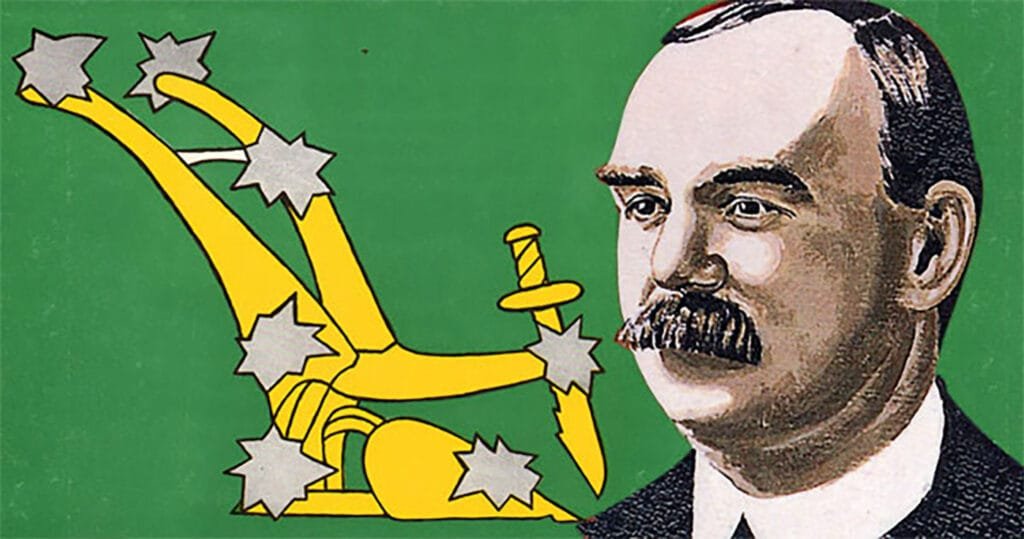

James Connolly was born in Scotland to Irish immigrant parents. Early on, he became involved in politics, adopting strong socialist convictions and becoming a firm believer in trade unions. He also supported the suffragette movement. His activism led him from Scotland to Ireland, where he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party. In America, he became part of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the “One Big Union.”

Eventually, Connolly returned to Ireland and joined James Larkin’s Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). Initially sent to Belfast to expand union operations, Connolly was called back to Dublin in 1913 to help lead major strikes. Dublin workers had joined the union en masse, much to the displeasure of their exploiters—sorry, employers. The result was one of the most significant industrial disputes in Irish history: the Dublin Lockout.

The Dublin Lockout

To set the context, imagine: you work 17 hours a day, with only one day off every 10 days. A hundred people live with you in a five-storey tenement, with one outhouse toilet for everyone. People are starving, suffering from malnutrition — this is not the Famine here, just plain exploitation. Infant mortality rate and tuberculosis-related deaths are off the charts. Dublin is the worker’s living hell. 1

So, naturally, they joined the union in numbers.

But the exploiters — sorry I keep making the same typo — saw the ITGWU as a dangerous, socialist revolutionary force. Workers were locked out unless they pledged not to join the union, and would be replaced by scab workers coming from Britain or other parts of Ireland. The ITGWU launched sympathetic strikes and received £150,000 in support from the British Trade Union Congress. Connolly organised a “kiddies’ scheme” to send malnourished children to sympathetic families in Britain. However, the Church — who was already siding with the employers — opposed the initiative, on the account that the kids would be sent to Protestant families. Or worse: atheists! Connolly cancelled the scheme but made sure to invite his people to ask the archbishop and priests for food and clothing.

The Irish Citizen Army

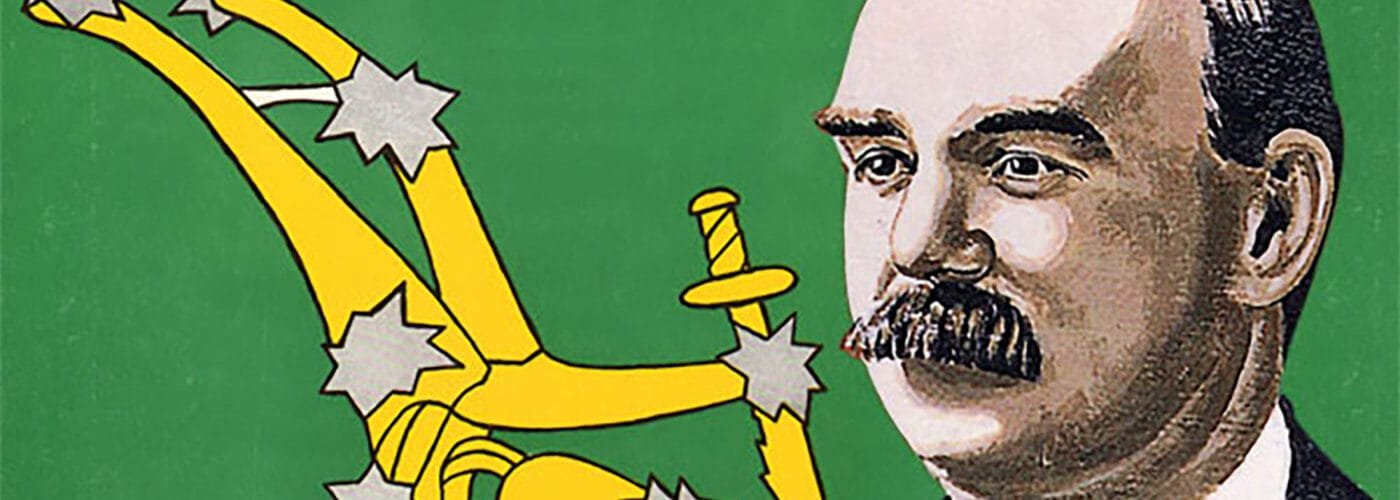

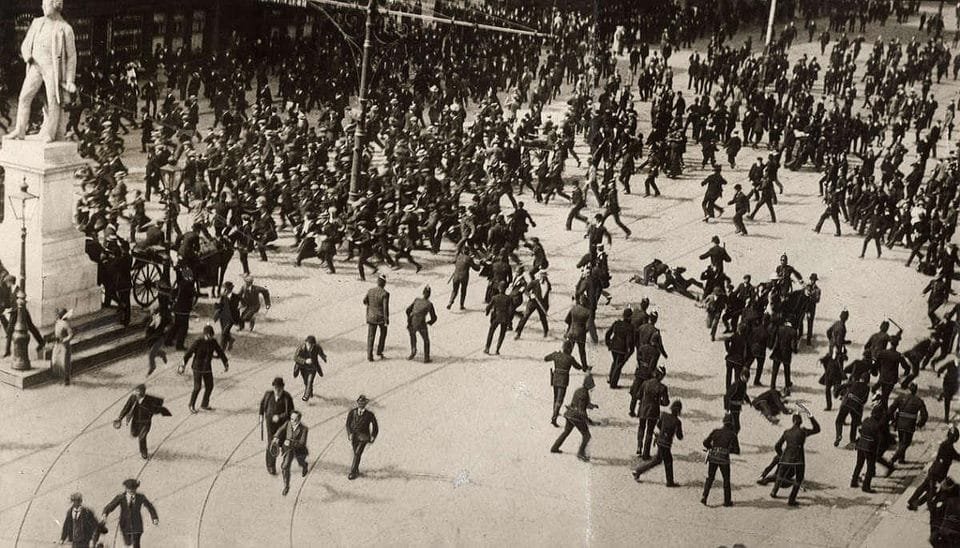

In August 1913, a peaceful rally turned violent: two workers were beaten to death by police, 300 were injured, and many arrested, including Connolly. This became known as the first “Bloody Sunday” of the 20th century. Connolly was released after a week-long hunger strike. As police violence and scab attacks continued, the ITGWU created a militia to defend workers at rallies: the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), with the Starry Plough as its flag.

The Lockout lasted from August 1913 to January 1914. At its peak, 100,000 workers were on strike. But with no national general strike in Britain and mounting hunger, the movement lost momentum. Many returned to work, signing the exploiters’ pledge. Others, jobless, joined the British Army and died in World War I under the command of the same people who had denied them dignity at home.

The Easter Rising

Connolly had long dreamed of a peaceful path to an independent Irish Socialist Republic—rallies, strikes, persuasion. But after the Lockout, he realised that change might require armed resistance. With Larkin in the U.S., Connolly became commander of the ICA. They trained, armed themselves, and waited.

In 1916, members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and the Irish Volunteers feared Connolly would launch a solo military action. They convinced him to join forces. On April 24, Connolly co-signed the Proclamation of the Irish Republic, launching the Easter Rising. After a week of fighting, the provisional government, based in the GPO, surrendered to prevent further civilian casualties. Connolly, commander of the Dublin Brigade, had been shot in the ankle and was carried out on a stretcher.

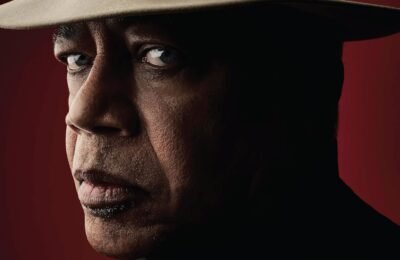

Weeks later, 16 republican leaders were court-martialled and executed. On May 12, 1916, James Connolly—unable to stand—was tied to a chair in Kilmainham Gaol and shot by a firing squad. He was 47. The day before, during his final visit with his wife, he said: “Well, Lillie, hasn’t it been a full life, and isn’t this a good end?”

“The One We Should Have Had”

So here we are. This is how a man who dreamed of a socialist republic—putting people before profit—went beyond his pacifist convictions in pursuit of justice. Becoming a martyr was the last thing he wanted.

Connolly was ahead of his time. A committed feminist, he believed that “if the worker is the slave of capitalist society, the female worker is the slave of that slave.” He refused to accept any “free” state that did not include the emancipation of women. The ICA welcomed women into its ranks and offered them equal opportunity to become officers.

Though raised Catholic, Connolly opposed clericalism and rejected Church influence over state and education. His loss—especially when compared to the conservative direction taken by De Valera’s post-civil war government—is still mourned. Against his will, he became a revolutionary hero and martyr figure, immortalised in songs like “The Ballad of James Connolly” by the Wolfe Tones.

Black 47’s Anthem for a Revolutionary

Black 47 was a Celtic rock band formed in New York by Wexford-born Larry Kirwan and Brooklyn policeman Chris Byrne. Named after the worst year of the Great Famine, the band fused traditional Irish instruments with electric guitars, reggae, and punk. Often associated with Irish republicanism, they tackled revolutionary history in their music.

Their song “James Connolly” is a great example. Kirwan explained:

“I hated the old standard song, ‘The Ballad of James Connolly.’ As a socialist myself, I resented that he had been railroaded by tears-in-the-beer nationalism. I thought that Connolly, the world revolutionary, would have resented that, too… I always have to find a way to enter his spirit.”

The Wolfe Tones depicted Connolly as a wounded victim of British imperialism. Black 47 focused on his convictions—on the man who fought for an Irish Socialist Republic. In their version, Connolly rallies his comrades to “fight for the rights of working man and the little farmer too.” In a moving spoken-word interlude, he addresses Lillie, expressing his will to live but confessing that he can’t endure any more—an allusion to the trauma of the Lockout.

Still singing for Connolly

James Connolly is such a fascinating figure; it’s no wonder he inspired so many artists. Poet Patrick Galvin wrote a tribute later recorded by Christy Moore and covered by the Black Family, focusing more on Connolly the union man.

Ultimately, Black 47’s song captures the essence of James Connolly: vibrant, passionate, and defiant. Many bands covered this song (see our playlist on the right). It makes you want to raise the Starry Plough and sing along.

Now I feel as rebellious as my beloved.

- https://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/exhibition/dublin/poverty_health.html or https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/articles/fourteen-dublin-corporation-members-own-tenement-houses ↩︎